|

[Home] [Events] [Gallery] [Publications] [Sidney St exhibition] [Join Jeecs] [Readers help] [Who's who] [Rosenberg]

Welcome to the

Jewish East

End Celebration

Society

Olives,

coocumbers and sammon sangwiches

HAROLD POLLINS

researches the story of the Netherlands Choral and

Dramatic Club, one of the many now forgotten Jewish

clubs that flourished in the East End1

In 1951 the veteran

journalist, Gabriel Costa – he had been writing for

the newspapers before the First World War and

continued to do so until the 1970s – published an

article entitled ‘The Dutch Club: a Vignette.’2

He described certain aspects of the vanished

Netherlands Choral and Dramatic Club. “At no time in

its variegated story,” he wrote, “had the Dutch Club

cherished ‘high-brow’ ambitions. Its mission was

frankly the entertainment of the jaded workers of

the Ghetto at a minimum of expense and with a

minimum of ‘trimmings’.”

It was a social club and,

in particular, he described the often raucous

reception of new plays put on at the club. The

actors would, inter alia, be interrupted by the

waiters’ loud inquiries of the audience: “Any

olives, coocumbers, sammon sangwiches?” Occasionally

the actors would be pelted with pennies but “olive

stones worked out cheaper”.

It is worth stating at

this point that doing research on this and other

Jewish clubs is difficult. Their records do not

appear to have survived and I have had to make use

of items in the Jewish and other newspapers as well

as the published reports of the Club and Institute

Union, to which some of the Jewish clubs belonged.

From them one can piece together at least the

outlines of the various clubs' activities.

Unfortunately there seem to be no lists of members,

but this is not surprising since members paid

monthly or weekly subscriptions and, with several

hundred people with fluctuating membership, it is

unlikely that accurate records would have been kept.

Costa was describing the

club’s later years.The Netherlands Club had begun

quite differently from the description he gave in

1951, coming into existence as the Netherlands

Choral Society on August 15,1869, at a meeting at

the Zetland Hall, 51 Mansell Street, a well-known

East End venue for meetings of all kinds.

The Choral Society had

been formed “For training choristers, and for giving

Entertainments in Aid of Charitable Institutions”.3

As befitted the Dutch origin of the members

(at first the language spoken was Dutch) it had a

title “Nut zy ons doel” (which may be translated as

“Good Intent” or “Usefulness is our Goal”).Another

title was “Ons Genoegen” (“Our Pleasure” or “Our

Content”.)

It

was indeed a choral society. Its conductor was the

renowned Julius Lazarus Mombach (1813-1880), for

many years choirmaster at the Great Synagogue and a

composer. Early in society’s life, the

Jewish Chronicle

reported that“at the funeral of one of its members,

the association, headed by the choir, marched to the

cemetery, singing very finely”.4 And a

few months later, onJuly 8, 1871, the

Jewish Chronicle

reported that “members of the Netherlands Choral

Society serenaded

Mr J. L. Mombach,

their conductor, at his residence, Finsbury Square,

in honour of the success which attended their first

public concert on Wednesday, 5th inst., at the New

Town Hall, Shoreditch. An immense crowd of persons

was attracted by the scene”.5

The second portion of the

club, the Dramatic part of the title, was formed

separately in 1881 and met at 25 Gun Street. The

1888-9 annual report of the Club and Institute

Union,

to which both

societies were affiliated, noted that both clubs

supplied alcoholic drink, and that neither provided

educational classes nor had a library (important,

for the CIU advocated education as a feature of

working men’s clubs). However the Choral Society did

provide, along with games, some lectures. The

Dramatic Society had no provision for lectures but

provided Sunday concerts and games.

This, though, was to

neglect some aspects of the Choral Society. For

example, Henry Hymans, a member of the Society,

obtained a certificate for excellence in the CIU’s

History examination and in 1885 the club won the

whist tournament held among London clubs.6

Soon after its formation

the Choral Society had moved from Zetland Hall to

nearby Vine Street but its new and permanent

premises (a former bottle factory) in Bell Lane,

Spitalfields, adjacent to the Jews’ Free School,

were opened formally on July 18, 1887, by Samuel

Montagu, Liberal MP for Whitechapel, beginning with

a consecration service.

Montagu congratulated the

club and spoke of the advantages of such an

institution “promoting cordiality and good

fellowship amongst the members, spreading a love of

music and harmony, successful rivalry to the

public-house – which, however, Jews need not much

fear – and, principally, its great Anglicising

influence”. He wondered, though, whether the word

Netherlands in the title was still appropriate since

the club had recently decided to conduct proceedings

in English and was now open to the English, Germans,

Poles and others.

He thought National would

be a better description and also suggested that

women members should be given the same rights as

males, as happened at the Jewish Working Men’s Club

(of which Montagu was the President).

A month later it was

announced that the premises would be used for

services during the forthcoming Yamim Noraim (the 10

days of repentance from Rosh Hashanah to Yom

Kippur).7

There is something of a

mystery about the two societies, the Choral and the

Dramatic, notably the date when they joined

together. A complaint of 1888 referred to the

“Netherlands Choral Club” in Vine Court (sic), in

the year following the opening of the Bell Street

premises. A letter in the

Jewish World

stated that chometz (leavened food) had been on sale

at the club during Passover, especially the sale of

beer. “Its sister institution in Bell Lane, as well

as other Jewish clubs, does without selling malt

liquor during Passover.”

On the previous Friday the

correspondent had found kosher refreshments on the

same bar as beer and biscuits. The following week J.

Hontman, the secretary, replied to the effect that

no visitors were allowed that day and that the club

was as strict as any others. The original

correspondent replied that Hontman had not denied

selling chometz and that, as the club was affiliated

to the CIU, it could not exclude visitors.8

Was the sister

institution in Bell Lane the Dramatic Society? But

Montagu had referred in 1887 to the club in Bell

Lane “spreading a love of music and harmony”,

sentiments more appropriate to a Choral Society.

At any rate by 1889 the

two societies had merged as the Netherlands Choral

and Dramatic Society – Montagu’s suggestion to

change its name had not been taken up and the new

name was used in a report that year of the formal

opening of an addition to the Bell Lane premises,

again presided over by Samuel Montagu. He announced

a proposal to add a lending library and promised £20

for the purpose.9 The club now occupied

24 and 25 Bell Lane.

One important feature of

the club, as with many other Jewish clubs affiliated

to the Club and Institute Union, was its close

association with non-Jewish clubs. It was very

common for members to visit other clubs for games

competitions, concerts or to socialise. One of the

unofficial club journals,

Club Life,

which began life in January 1899, contained a very

appreciative article on the Netherlands Club in its

sixth issue, entitled Clubs You Should Visit.

Interestingly it ended an

interview with the vice-president,I.

Danziger, saying:“‘Git

morrgen, Rabbi Pip.-Pip. Mozill to

Club Life’,

or words to that effect.”10 Part of the

article was an interview with Mr Danziger, who was

asked by the interviewer about Yiddish and wrote

some down for him, in Hebrew characters.

On the other hand

a

Jewish Chronicle

item about the

club in 1913 stated that “Yiddish is seldom heard

within its precincts.”11

Perhaps it was true by

then.

As well as concerts,

games and alcohol the club did other things. It ran

a tontine fund for sick and funeral benefits and

subscribed to the Jewish Soup Kitchen Fund. It was

non-political but, according to Club Life in 1899,

it was “a great factor for the Liberal cause”. It

also contributed to the CIU’s Convalescent Home and

ran parties for children, a common feature of many

workingmen’s clubs. 12

The leading light in the

club was Samuel Strelitski, president for many

years. He wasborn about 1833 in Amsterdam, according

to the 1871 Census in which he is described as a

tailor. He arrived in Britain in the early 1850s; in

1904, after 52 years in Britain, he was created

Knight of the Order of Orange Nassau by the Queen

and government of the Netherlands. The

Jewish Chronicle

described this award as recognition of his being

“regarded as the unofficial head of the Dutch Jews

in the East End of London”.

13

The Netherlands Club was

one of the two largest Jewish social clubs in the

East End, the other being the Jewish Working Men’s

Club in Great Alie Street. This had been founded,

probably by Samuel Montagu, in 1874, following the

establishment in 1872 by the Jewish Association for

the Diffusion of Religious Knowledge (of which

Samuel Montagu was president) of the Reading Rooms

in Hutchison Street. These had been intended to

provide an alternative for young men who would

otherwise frequent public houses and desecrate the

Sabbath.

Two years later it became

a Working Men’s Club, and in its heyday, in

purpose-built premises in Great Alie Street, a major

centre for all sorts of Jewish communal activities,

including a major Zionist meeting with Theodor

Herzl. Unusually for such a club it had women as

full members, and it did not allow alcoholic drink

or, for most of its life, even card-playing

(gambling, said its founders, being the Jewish

vice.) It provided lectures and debates and numerous

sub-clubs, such as one for cycling. But towards the

end it seemed to concentrate on dances and on

providing Gilbert and Sullivan operas.14

The heyday of the

numerous East End Jewish social clubs was before the

First World War, and some had only an ephemeral

life. The Jewish International Working Men’s Club,

19 Great Prescott Street, lasted only a year or two

from 1890; the United Jewish Club, Aldgate Avenue,

failed about a year after its foundation in 1896;

the Jewish Social Club, formed in 1891, was located

in at least four different premises in its lifetime,

until it closed in 1905. Others disappeared during

and after the war. The Judaean Social and Athletic

Club, at first at 3 Johnson’s Court, Leman Street,

and then at 54 Prince’s Square, Cable Street, lasted

from 1907 to 1916.15

The Netherlands Club’s

reached just over 1,000 in 1901 but by 1910 was just

below 600. The Club, it seems, lasted until 1932.

Its demise, and that of the other clubs, may be

attributed to the fairly obvious causes – the

beginnings of the decline of the Jewish population

of the East End and, especially, the provision of

newer and alternative forms of leisure pursuits.

These included the cinema, the radio and the

gramophone. Moreover, the benefits provided by the

clubs began to become available from the state.

Some East End clubs

certainly flourished, however. The Old Boys’ Club,

in the Mile End Road, was one and another was the

Oxford & St George’s, run by Basil Henriques (which

celebrates its centenary in 2014). The Netherlands

Club, nevertheless, is certainly worth recalling as

a significant feature of the East End and especially

of its Dutch component.

----------

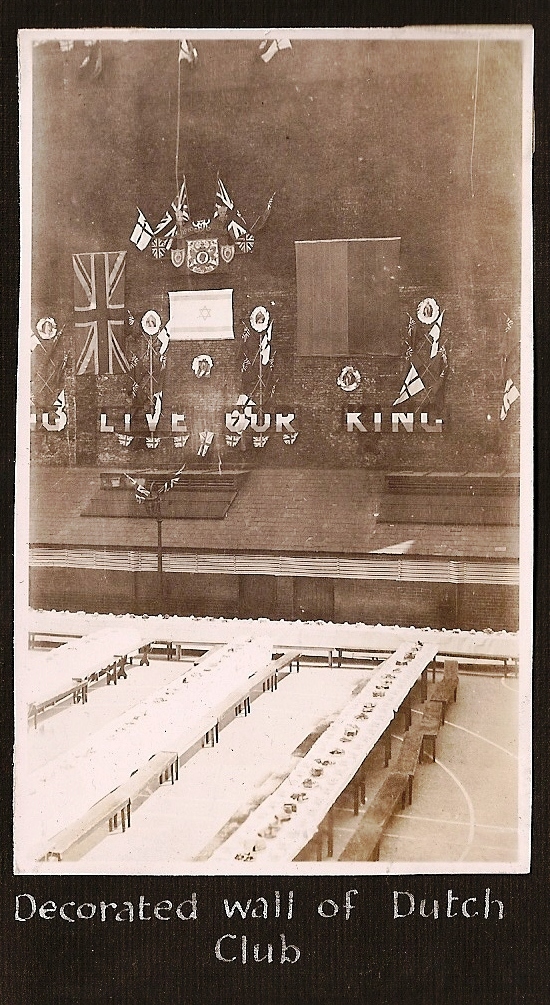

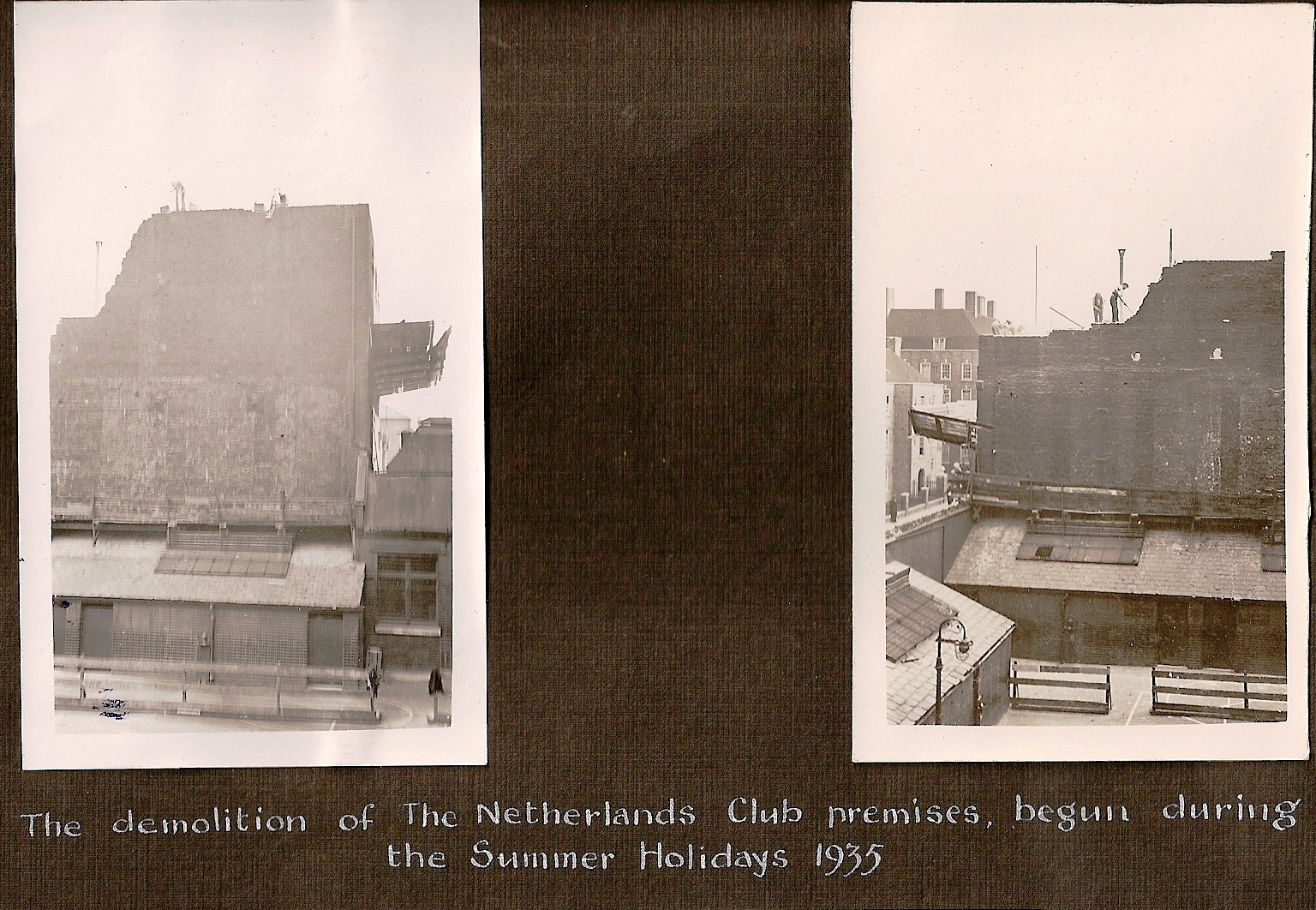

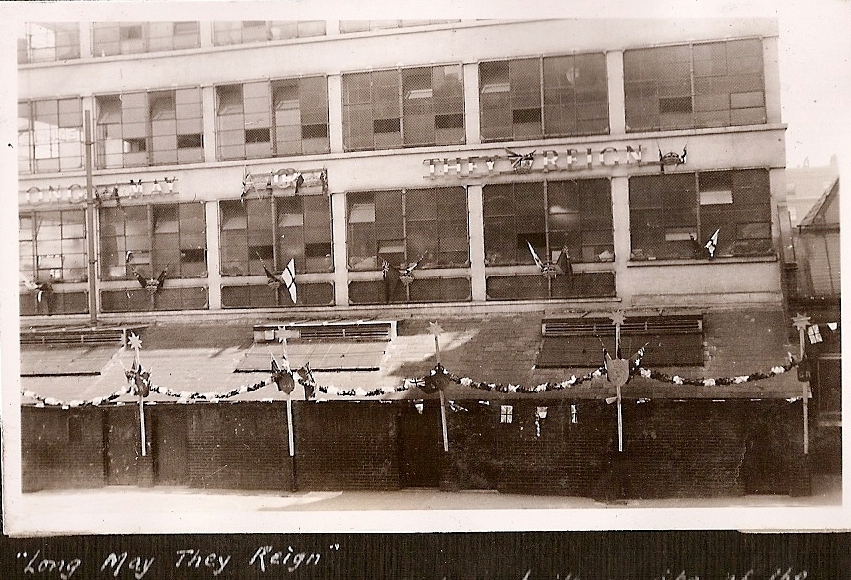

The photos below are from an album given to

me by my late friend Joan Rich, daughter of Julius

Rich, a former teacher at Jews Free School, Bell

Lane, London E1

Above,

decorated wall of the Netherlands club for Jews Free

School's George 5th Silver

Jubilee celebrations, 8 July 1935, viewed from the

playground of Jews Free School, Bell Lane. The

foreground shows tables laid for their celebration

feast.

Above, the demolition of the

Netherlands club, begun during Jews Free School's

Summer holidays in 1935

Above, the demolition of the

Netherlands club, begun during Jews Free School's

Summer holidays in 1935

Above,

'Long may they reign', 1936 Edward 8th

Coronation decorations displayed on factory built on the

site of the Netherlands club that was demolished Summer

1935, viewed from the playground of Jews Free School,

Bell Lane

|

|

1This

article was originally published in

Shemot, vol 10 no

1, March 2002, and is reproduced by permission of

the author. An earlier version appeared in Harold

Pollins’article 'East End working men's clubs

affiliated to the Working Men's Club and Institute

Union, 1870-1914', in

The Jewish East End 1840-1939 (Proceedings of the

conference held on 22 October 1980 jointly by the

Jewish Historical Society of England and the Jewish

East End Project of the Association for Jewish

Youth, 1981)

edited by Aubrey Newman, pp. 182-186.

2Jewish

Chronicle,

10 Aug 1951. He had, inter alia, published an

article in the

JC on 13 Mar 1914,

'Purim in Spitalfields', which included the

statement:“I have a very enjoyable recollection of a

Purim masquerade ball celebrated at the Netherlands

Club in Bell Lane.” Manifestations of “'outward

gaiety”, he said, had occurred up to 10 years

before.

3A.I.

Myers (compiler),

The Jewish Directory for 1874

(1874), p. 53.

4JC

Feb17, 1871,

p. 11

5JC

July 14, 1971, quoted in

Doreen Berger,

The Jewish Victorian,

1999, pp.395-6.

6JCJun9,

1883, p.12; May 22, 1885, p. 7

7JC

Jul22,1887, p.10; Aug 19, 1887, p. 1. This July

report was entitled 'The Netherlands Working Men's

Club.'

8Jewish

World Apr6,

1888, p.3; Apr 13, p. 3; Apr 20, p. 3.

9JC

Oct 18, 1889, p. 7

10Club

Life Feb11,

1899, pp.1-2.

11JC

Sep5, 1913,

p. 23. From the style the item was probably written

by Gabriel Costa.

12Club

Life Feb18,

1899.Page 9 had a description of a party for 1,000

children given at the club.

13He

was the Samuel Streletskie (sic) referred to by

Doreen Berger in

The Jewish Victorian,

page. 554. He was the son-in-law of Moses Boam,

Superintendent of the Soup Kitchen for the Jewish

Poor.

14See

Harold Pollins,

A History of the Jewish Working Men's Club &

Institute 1874-1912,

Ruskin College Library Occasional Publication No. 2,

Oxford, 1981.

15Details

from the CIU records

|

|